COVID-19 Forecast for El Paso County – June 22

Plus, our resident microbiologist on mutations and vaccine creation

Good morning, and happy Monday. On this pre-pandemic date last year, the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College was hosting a “Sashay” event to celebrate pieces of wearable art from a visiting collection. (Currently, the FAC is temporarily closed, but offering virtual classes.)

Today, Phoebe Lostroh returns to give her weekly COVID-19 forecast for El Paso County and to explain why it’s important that the virus is mutating. Lostroh is a professor of molecular biology at Colorado College on scholarly leave who is serving as the program director in Genetic Mechanisms, Molecular and Cellular Biosciences at the National Science Foundation. She recently won the 2019 Taylor & Francis award for “Outstanding New Textbook” in the science and medical category for her book, “Molecular and Cellular Biology of Viruses.”

➡️ICYMI: On Friday, we summarized a planning guide for higher-ed administrators and more announcements from liberal arts colleges.

Phoebe’s Forecasts

NOTES: These forecasts represent her own opinion and not necessarily those of the National Science Foundation or Colorado College. She used the public El Paso County dashboard for all data.

⚖️ How her predictions last week shaped up: June 20 is the last day of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report week 25 in the national public health calendar. It was also the beginning of the 16th week since the first case was detected in El Paso County; 116 EPC residents have died of COVID-19 since March 13. Last week, using the most recent trend (“best guess”), I forecasted 2,061 cumulative reported cases as of June 18 and in reality, there were 2,065 reported cases.

From May 29 to June 14, the number of new cases reported each day was in decline. But this trend reversed in the last week. Newly reported cases are about the same across Colorado this week compared with last week when averaged across all counties.

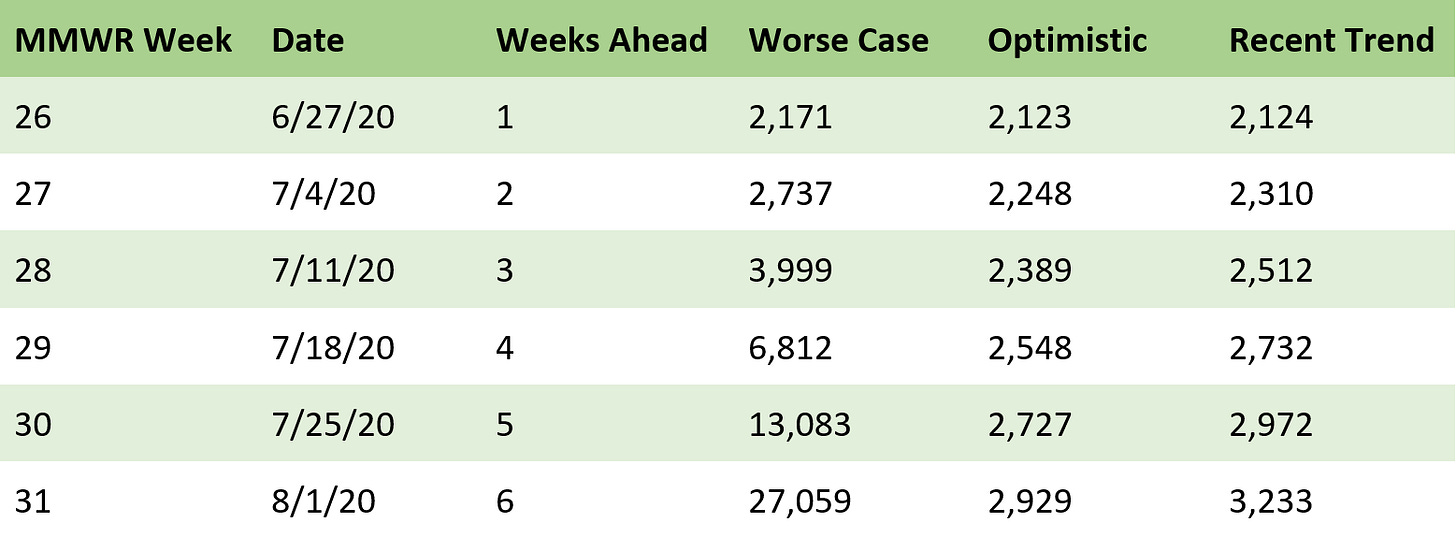

Predicted cumulative reported cases in El Paso County

Predicted new COVID-19 reported cases in El Paso County

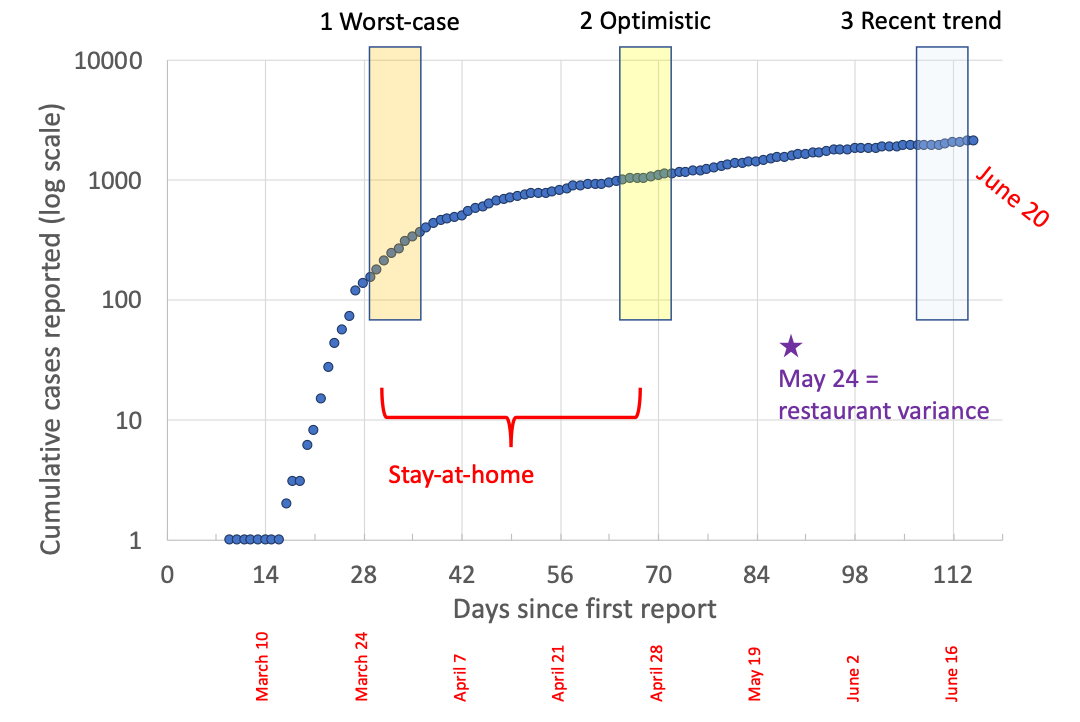

Cumulative reported cases

🗝️ Key points: Cases are recorded on the day they were reported to the county, not on the day the person first exhibited symptoms; this information is only known for 85% of cases, so we use the reported date instead.

Forecast based on stages 1, 2, and 3

🗝️ Key points: The trend from last week was that new reported cases were decreasing, whereas this week, that trend has seemingly reversed. The forecast this week has greater uncertainty than usual, because some cases are trending downward and some are trending upward.

Reported cases by MMWR week

🗝️ Key points: We saw a drop in new cases per week from weeks 22-23 and held steady from weeks 23-24. This result was unexpected because the restaurant variance seems to be associated with a reduction in cases two weeks later, rather than an increase. We see a dramatic increase in cases reported during week 25 compared with week 24 — greater participation in testing accompanied this increase in cases, so the percent testing positive has remained about the same.

Testing and positivity rate in El Paso County in each week

🗝️ Key points: At the beginning of the outbreak, tests were severely rationed — offered only to healthcare workers and patients who needed hospitalization — and resulted in a high percent positivity. Testing populations much more broadly, including tests of people who do not have symptoms, is one of the few interventions shown to be effective in controlling the epidemic.

14-day incidence using reported cases

🗝️ Key points: Another way to try to predict how the number of newly-reported cases will change in the short term is to consider the 14-day incidence, which requires adding up all cases reported in 14 days and dividing by 7.15 (because there are 715,000 Springs residents). The horizontal dotted lines show the thresholds the Colorado Department of Public Health uses to make policy decisions. If people hadn’t complied with Stay-at-Home, we probably would have reached the “high” threshold about April 21. If the reported cases continue to trend upward as they have for the most recent four days, we will reach the “medium” threshold — higher than we have ever been — by the end of the month.

Q-and-A with Lostroh: The coronavirus is ‘mutating.’ What does that mean?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

CC COVID-19 Reporting Project: Let’s start with some information we’ve seen about how the virus is mutating.

Lostroh: Any biological evolving entity as they reproduce, viruses will accumulate random mutations — mutations that occur at random, changes to their genetic code that occur at random — and then most of those will have no effect on how well the offspring virus that got that mutation reproduces. But some will be detrimental to how well it reproduces, and those we won't be able to find in a survey of the population because they don’t leave many descendants, but some we’ll find more frequently than we ought to than on average. And those mutations then are suspected as contributing to some kind of benefit to the virus, relative to its parents, and so recently they have found some mutations that encode changes in the part of the virus that interacts with host cells in order to get inside them. And this mutation seems to make it possible for the virus to spread further within a single person’s body and to be transmitted more efficiently to other nearby cells.

So, that’s a concerning change. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the virus is more deadly, but it could mean that mutant is going to spread through human populations faster than it otherwise would. And the thing about evolution is that the way to combat it is to try to slow reproduction. Since these mutations occur at random, as a consequence of reproduction, the lower the number of viruses that are out there reproducing, the slower evolution toward something different that we’re not ready to deal with will be.

CCRP: How could these mutations affect vaccine creation for this coronavirus?

Lostroh: So any mutations that could alter the surface then could actually affect how well a virus can evade antibodies that are provoked by any immunization strategy. And there’s always a lag between deciding what vaccine to synthesize, and then manufacturing it on a massive scale to get millions and millions of doses, and then actually giving it out. And if the virus is reproducing and evolving all that time, then the virus can evolve mutations that will make the vaccine less effective. Because the virus that will be in circulation nine months later, its surface is just genetically distinctive enough compared to the virus we put in culture nine months ago to manufacture the vaccine so that it can escape from the immune reaction to the vaccine virus. So that’s what we’re trying to avoid here with SARS coronavirus-2.

CCRP: Could this coronavirus become seasonal, like the flu?

Lostroh: We really don’t have a good measure for how fast coronaviruses evolve when they are extremely abundant as this one is likely to become, and we have a lot less information about the seasonality of coronaviruses than we do flu. So there’s some information coming out of studies in Australia and China that humidity could affect coronavirus transmission, this coronavirus in particular, in which case that could contribute to some kind of seasonality. But in terms of the pace of evolution and how it interacts with the majority of people’s immune systems in the population, we just don’t know that much about it yet, but it could become seasonal. Or just present, you know.

For the SARS-1 virus, I think that most people who got SARS-1 and survived it still had about half of the antibodies in their system, but two years later, they had half as many antibodies than they did when they were first infected. That's really a low amount of antibody persistence for a viral infection. And so, extending from that experience, that would mean that, probably, those people were not that immune to SARS-1 if it had come back. So we don’t know whether it’s possible to provoke a longterm immune reaction that can protect someone from SARS coronavirus-2 for longer than a few years, but based on SARS-1, it’s not very hopeful. And if that’s the case then SARS coronavirus-2 could sort of be around all the time, but we would just have to get immunized regularly like we do with influenza.

CCRP: Are screening measures, like temperature checks, effective measures to prevent COVID-19 spread?

Lostroh: There’s absolutely no evidence that those surveys have any effect whatsoever on the spread of the virus. And the same with taking the temperature. In fact, there’s even a study that hasn’t been peer-reviewed yet, but it’s out of a bunch of hospitals in Boston, basically showing that hundreds of thousands of people who come to the ER are much less likely to have a fever in the morning than they are at night, even if they have something that causes a fever.

So screening people when they arrive at work or school in the morning for fever is not a good way to catch temperatures, or to catch people who are sick. Also, there are good studies of how effective it is to screen people at an airport when they’re traveling with surveys and temperature — and the answer is completely ineffective because they usually don't have a fever yet, and almost everybody who is spreading it hasn’t got enough symptoms to even notice. So they’re just pre-symptomatic and therefore aren’t reporting, so it sounds like temperature screening and symptom surveys are not going to be an effective measure of control. But at the same time, every single plan I read for every business and every school says, ‘we’re going to do symptom checks and temperature screens.’ That might make us feel better, but I don’t know if it’s very effective.

About the CC COVID-19 Reporting Project

The CC COVID-19 Reporting Project is a student-faculty collaboration by Colorado College student journalists Miriam Brown and Arielle Gordon, Journalism Institute Director Steven Hayward, Visiting Assistant Professor of Journalism Corey Hutchins, and Assistant Professor of English Najnin Islam. Work by Phoebe Lostroh, Associate Professor of Molecular Biology at CC and National Science Foundation Program Director in Genetic Mechanisms, Molecular and Cellular Biosciences, will appear from time to time, as will infographics by Colorado College students Rana Abdu, Aleesa Chua, Sara Dixon, Jia Mei, and Lindsey Smith.

The project seeks to provide frequent updates about CC and other higher education institutions during the pandemic by providing original reporting, analysis, interviews with campus leaders, and context about what state and national headlines mean for the CC community.

📬 Enter your email address to subscribe and get the newsletter in your inbox each time it comes out. You can reach us with questions, feedback, or news tips by emailing ccreportingproject@gmail.com.