COVID-19 Forecast for El Paso County — Sept. 14

Plus, our resident microbiologist on how COVID-19 could get into a person’s brain

Good morning, and happy Monday. On this pre-pandemic date last year, Colorado Springs residents were attending the annual Van Briggle Pottery Festival, co-presented by the Fine Arts Center’s Bemis School of Art. (The Fine Arts Center is currently closed to the public.)

Today, Phoebe Lostroh returns to give her weekly COVID-19 forecast for El Paso County and to explain why a COVID-19 vaccine trial was recently suspended. Lostroh is a professor of molecular biology at Colorado College on scholarly leave who is serving as the program director in Genetic Mechanisms, Molecular and Cellular Biosciences at the National Science Foundation.

➡️ICYMI: On Wednesday, we explained how student employment and financial aid will work for the fall semester. We also recapped the town hall about the new fall plans, and we profiled three students who have alternate plans for this fall.

Phoebe’s Forecasts

NOTES: These forecasts represent her own opinion and not necessarily those of the National Science Foundation or Colorado College. She used the public El Paso County dashboard for all data. Lostroh prepared these forecasts on Sept. 12.

⚖️ How her predictions last week shaped up: Sept. 12 is the last day of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report week 37 in the national public health calendar. It is the 27th week since the first case was detected in El Paso County. Since March 13, 160 El Paso County residents have died of COVID-19. Last week Lostroh predicted between 6,032 and 6,312 cumulative cases reported as of Sept. 10, and in actuality, there were 6,338. In El Paso County, the rate of new cases has continued to decrease. El Paso County has about 60% fewer cases reported in the last seven days compared with the previous seven days, Lostroh says.

Predicted cumulative reported cases in El Paso County

🗝️ Key points: Lostroh predicts El Paso County will probably see a total number of cases somewhere between the declining number of daily cases and the linear curve-fit this coming week because percent positivity for nasal swab testing continues to decline and is now below 3%. That would mean between 6,397 and 6,541 cumulative reported cases as of Sept. 17.

Reported cases in clusters connected to schools and businesses

🗝️ Key points: El Paso County defines an outbreak as two or more confirmed cases within 14 days at the same facility. Although the frequency of outbreaks at long-term care facilities has not increased, the frequency and number of cases associated with outbreaks at schools and businesses has increased. Between MMWR weeks 14 and 25, around 11 weeks had no outbreaks outside of long-term care facilities. Between weeks 26 and 37, only two of 12 weeks had no such outbreaks. Lostroh calculated these totals from Thursday to Wednesday because the state updates the outbreak data once a week on Wednesdays.

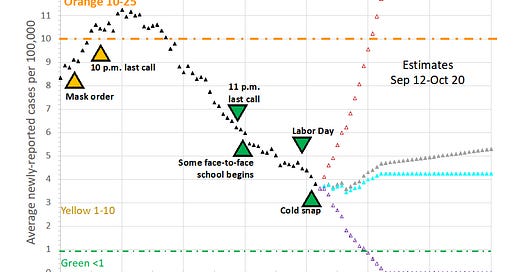

14-day rolling average of daily new cases per 100,000 people in El Paso County

🗝️ Key points: The Harvard University Global Health Institute suggested the thresholds Lostroh uses in this forecast. El Paso County has been in the yellow zone for about two weeks, and Lostroh expects the county to stay in the yellow zone for two more weeks, meaning that grades K-8 are safe to meet in person if pandemic-resilient buildings, classrooms, and practices are in place. Lostroh even predicts the county could achieve the green zone — where all grades and universities are able to meet in person if the buildings and practices are designed for safety — by Sept. 22.

Total nasal tests reported and rolling percent positivity

🗝️ Key points: El Paso County has been beneath the 5% positivity threshold for almost a month. There was a dip in the number of tests reported on and around Labor Day, with only 188 tests reported on Labor Day and 379 on the day after. Until then, the daily average was around 725 tests reported.

Total reported COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths

🗝️ Key points: Hospitalizations increased steeply at the same time reported cases did, namely from the end of June until the middle of August, but the rate of reported deaths has not been as steep since the first two months of the pandemic.

Q-and-A with Lostroh: Our resident microbiologist on how wastewater testing works

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

CC COVID-19 Reporting Project: In last week’s Town Hall, Brian Young, CC vice president for information technology, said the college has kits to test wastewater. Where is the science on wastewater testing?

Lostroh: I would say the science on that has moved really quickly because it’s so convenient and such a great warning system. It really is just using the same technology that you use on a nasal swab — you’re just using it on a water sample instead. Very early on, from studying cruise ship patients, we knew that you could detect the viral RNA in their stool, but we didn’t know whether or not the virus there was infectious. Now there’s kind of mixed evidence. This is why people are avoiding public toilets, and you should close the lid and things like this because there might be a little bit of infectious virus in there. But we know for sure there’s lots of viral RNA in there for people who are infected. The idea would be if you could collect a sample of water leaving an individual dorm, then you would know when there’s that RNA for the virus in the sample and then you could test everybody in the dorm in sort of a targeted way. I mean, people visit dorms, it’s not like everybody who uses the facilities in a dorm actually lives in that dorm, but it still has a good screening method.

CCRP: What should we know about AstraZeneca, the company that paused its vaccine trial after a volunteer developed an “unexplained” illness?

Lostroh: They had a reaction that is called transverse myelitis, which is like an inflammation of the spinal cord. That’s a pretty serious reaction. Now, people can get that because they have some other illness that they didn’t know they had before they participated in the vaccine trial, or it is a rare effect of some vaccines. So now they need to investigate the timing of it and all kinds of aspects of it to see whether or not she could have gotten it from the vaccine. They have already verified in the press that she did in fact receive the vaccine and not a placebo. So that was the first step. ... This vaccine is based on essentially an adenovirus that infects other animals. I think it’s a chimp adenovirus, and they genetically engineered it to express the coronavirus spike protein. So it has many other parts of an adenovirus in it that can also cause an immune reaction. And that’s actually intentional and good because you want the body to recognize the vaccine as both foreign and reasonably dangerous so that you provoke a strong immune response, but it can be bad if that causes these unanticipated effects that can happen sometimes with a vectored vaccine. So I don’t know how long this is going to take. I’m sure that they are going as quickly as they can, but it’s really important to establish whether it could have been caused by the immunization and if so, make plans for what to do next because a very rare complication can happen. ... But this is a very normal occurrence in any kind of vaccine development because we don’t have the ability to predict how a possible vaccine will work in the human body.

CCRP: Let’s talk about reports of potential long-term effects of COVID-19. How might this coronavirus affect the brain?

Lostroh: It’s very typical for pathogens to not be able to cross into nervous tissue. There’s a physiological mechanism called the blood-brain barrier. And usually what infectious disease specialists assume is that unless a virus or bacterium has some special ability to cross into the nervous system, that usually doesn’t happen. Whenever there’s a newly emerged infection there’s always this hope that it’ll probably be like most other pathogens, but then, what if it turns out it can cross into the nervous system? It’s looking like we need to investigate coronavirus infection and nervous tissue a little bit more. ... I am familiar with a study where someone has used stem cells in the lab and treated those stem cells with various signals to induce them to differentiate into nervous tissue. And they call this an organoid — it’s kind of like a laboratory version of sort of a brain — and they can indeed see SARS-coronavirus-2 replicating in this neural organoid tissue. They are arguing that therefore, the virus could possibly get into the nervous system.

About the CC COVID-19 Reporting Project

The CC COVID-19 Reporting Project is created by Colorado College student journalists Miriam Brown, Arielle Gordon, and Isabel Hicks, in partnership with The Catalyst, Colorado College’s student newspaper. Work by Phoebe Lostroh, Associate Professor of Molecular Biology at CC and National Science Foundation Program Director in Genetic Mechanisms, Molecular and Cellular Biosciences, will appear from time to time, as will infographics by Colorado College students Rana Abdu, Aleesa Chua, Sara Dixon, Jia Mei, and Lindsey Smith.

The project seeks to provide frequent updates about CC and other higher education institutions during the pandemic by providing original reporting, analysis, interviews with campus leaders, and context about what state and national headlines mean for the CC community.

📬 Enter your email address to subscribe and get the newsletter in your inbox each time it comes out. You can reach us with questions, feedback, or news tips by emailing ccreportingproject@gmail.com.